A Conversation With Gaia Rajan

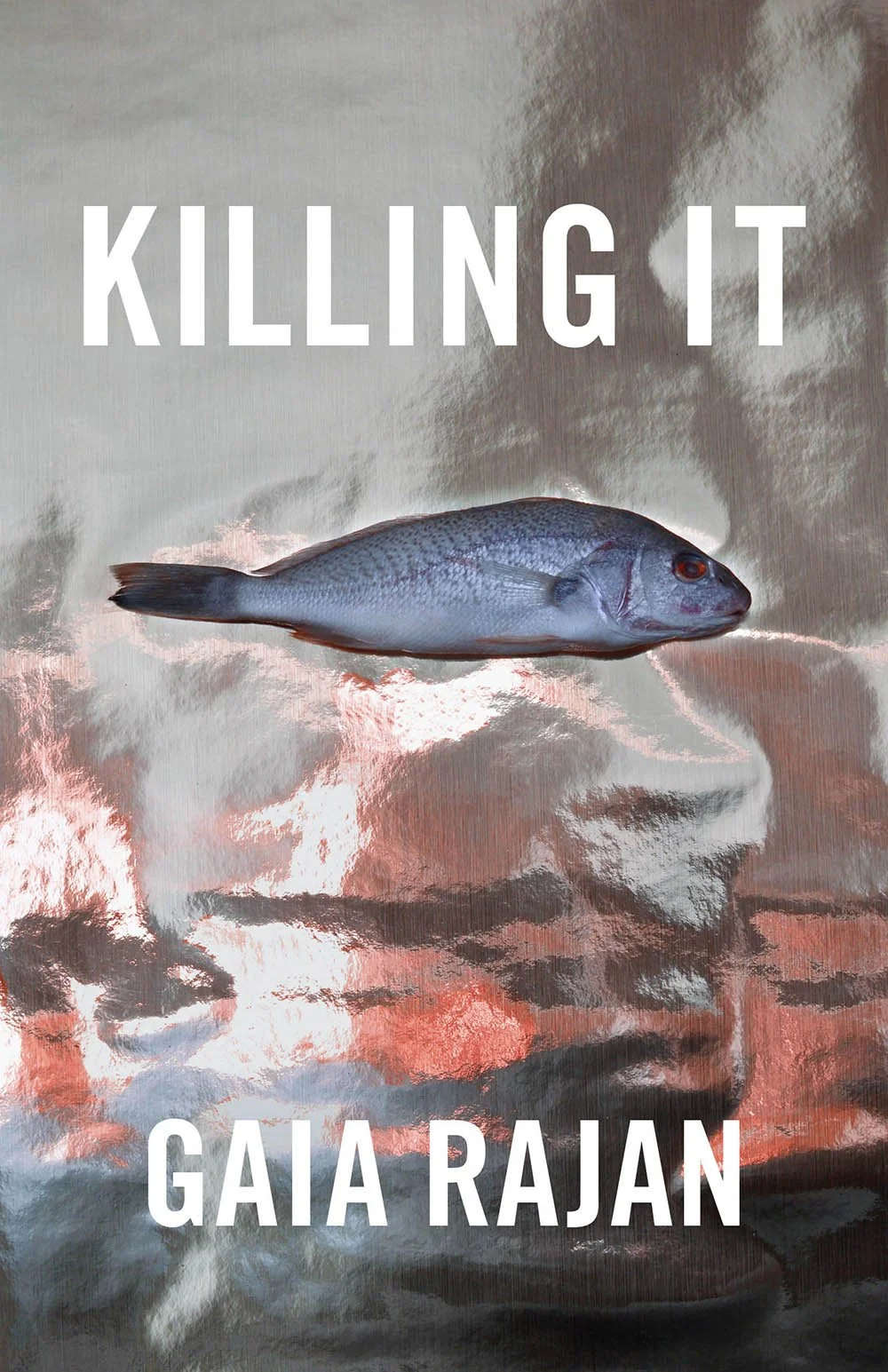

Gaia Rajan is the author of the chapbooks Moth Funerals (Glass Poetry Press 2020) and Killing It (Black Lawrence Press 2022). Her work is published or forthcoming in Best New Poets 2022, the 2022 Best of the Net anthology, The Kenyon Review, THRUSH, Split Lip Magazine, diode, Palette Poetry, and elsewhere. Gaia is an undergraduate at Carnegie Mellon University, studying computer science and creative writing. She lives in Pittsburgh. You can find her at @gaiarajan on Twitter or Instagram.

by Bella Rotker

I recently had the privilege of interviewing Gaia Rajan about her new chapbook, Killing It, (Black Lawrence Press, 2022) as well as her thoughts on the nature of identity and of poetry. Rajan was a Winter 2021 PATCHWORK fellow and author of Moth Funerals (Glass Poetry Press, 2020). Read on for her thoughts on the culture of American achievement, the writing process, the writer in relation to violence, and more.

Bella Rotker: Can you speak as to your experience in working on this chapbook? Did you set out to write a collection or did you write the poems individually and then piece them together?

Gaia Rajan: I think in units of collection, so I have months where I’m not writing, just planning a complete work, and then I write the whole thing from start to finish. Planning for me looks like creating “syllabi” for myself of different experiences that could interlock with what I’m trying to build—not just poetry, but museums, galleries, films, diary entries, thrift stores. And then, slowly, the universe of the collection comes together in my head. That’s roughly what happened for Killing It, though I entirely reimagined the movement of the collection during revision.

BR: Killing It focuses a lot thematically on queer Asian American identity, and the culture of American achievement. What motivated this project, and how do you see these poems and themes fitting together?

GR: I’ve spent a lot of time trying very hard to be good. At first I honestly believed it was possible for me to reach it—that if I denied myself enough I might reach purity in the eyes of institutions or just America as a whole. I wanted to be powerfully, incontrovertibly real. Or, I wanted to be a good Asian, a good subject, quiet enough to be seen as human. I wasn’t raised Catholic, but it’s a very Catholic idea, the hope that enough guilt might liberate you.

And then I realized I was queer. And then it became obvious to me that the fact of my body, my desire, made it impossible for me to be incontrovertible. That’s when I started writing Killing It.

BR: How do you approach titling poems? Does it come before or after the writing of the poem itself? What job does the title do in your eyes?

GR: I think the title for me is about the poem’s relationship with the reader—titles can reach out to the reader, but sometimes, they’re also meant to be oblique, to require effort for engagement. It really depends. I usually codename poems during drafts, and then the title comes later.

BR: What challenges did you run into while drafting this chapbook?

GR: I really struggled with the violence of my images—I worried a lot that I was using real physical violence to describe emotional experiences and by turning to that I was using the same linguistic tricks that’ve been used by people in power for ages to minimize actual, felt violence. So on draft two, I gutted the entire chapbook with the intention of reexamining my relationship to violence in my poems. The truth is, being in my body is, yes, often violent, but also beautiful. Also liberating.

I think one of the scariest things to me about The Poetry World is how often many poets, especially academic poets, turn to physical violence as shorthand without thinking critically about it. I watched a white poet invoke the language of “dead Asian bodies” on a stage to describe colonialism, and it was genuinely terrifying. I think we owe it to ourselves to really interrogate our relationship with metaphorical violence.

BR: You use whitespace, form, and lineation in really interesting ways. Can you talk about what prompted the variation in formal decisions between pieces? How do you decide on a form for a particular poem and then when would those formal decisions come in your writing process?

GR: The form usually came at the same time as the rest of the poem—I try not to impose a form on a piece unless it feels like it’s “asking” for it. I was thinking a lot about how to capture silence. Each form has a different relationship to silence. Prose poems are an expression of resolute interiority, and the silence is implicit in the space outside the dense lines. Staggered lines bring the silence to the foreground. In the ghazal crown in the center of Killing It, the silence is between stanzas of each individual ghazal, and stronger in the space between interlocked ghazals.

BR: Are there any authors that have inspired you in the process of writing Killing It?

GR: Yes, I really love Franny Choi's work—I'm so excited for her new book. And Essy Stone, and Jameson Fitzpatrick, Taylor Johnson, Rachel McKibbens, Luther Hughes. This book wouldn’t exist without Bhanu Kapil’s Schizophrene (I got to hold a first edition at Poets House and almost cried).

Bella Rotker (they/she) is a sophomore at the Interlochen Arts Academy where they major in creative writing. She was born in Caracas, Venezuela and grew up in Miami. They have received recognition from the Scholastic Art and Writing Awards and was a finalist in the Charles Crupi Memorial Poetry Contest. She won the Haley Naughton Memorial Scholarship to Iowa Young Writers Studio. Their work has appeared or is forthcoming in The Red Wheelbarrow, Crashtest, Hyacinth Review, Lumiere Review, Full Mood Mag, and Healthline Zine, among others. Bella can usually be found trying (and failing) to pet bunnies, pressing flowers, or staring wistfully at bodies of water.