Review of "Mother/land": At the Borders of Languages and Legacies

Review of Mother/land:

At the Borders of Languages and

Legacies

by Esther Sun

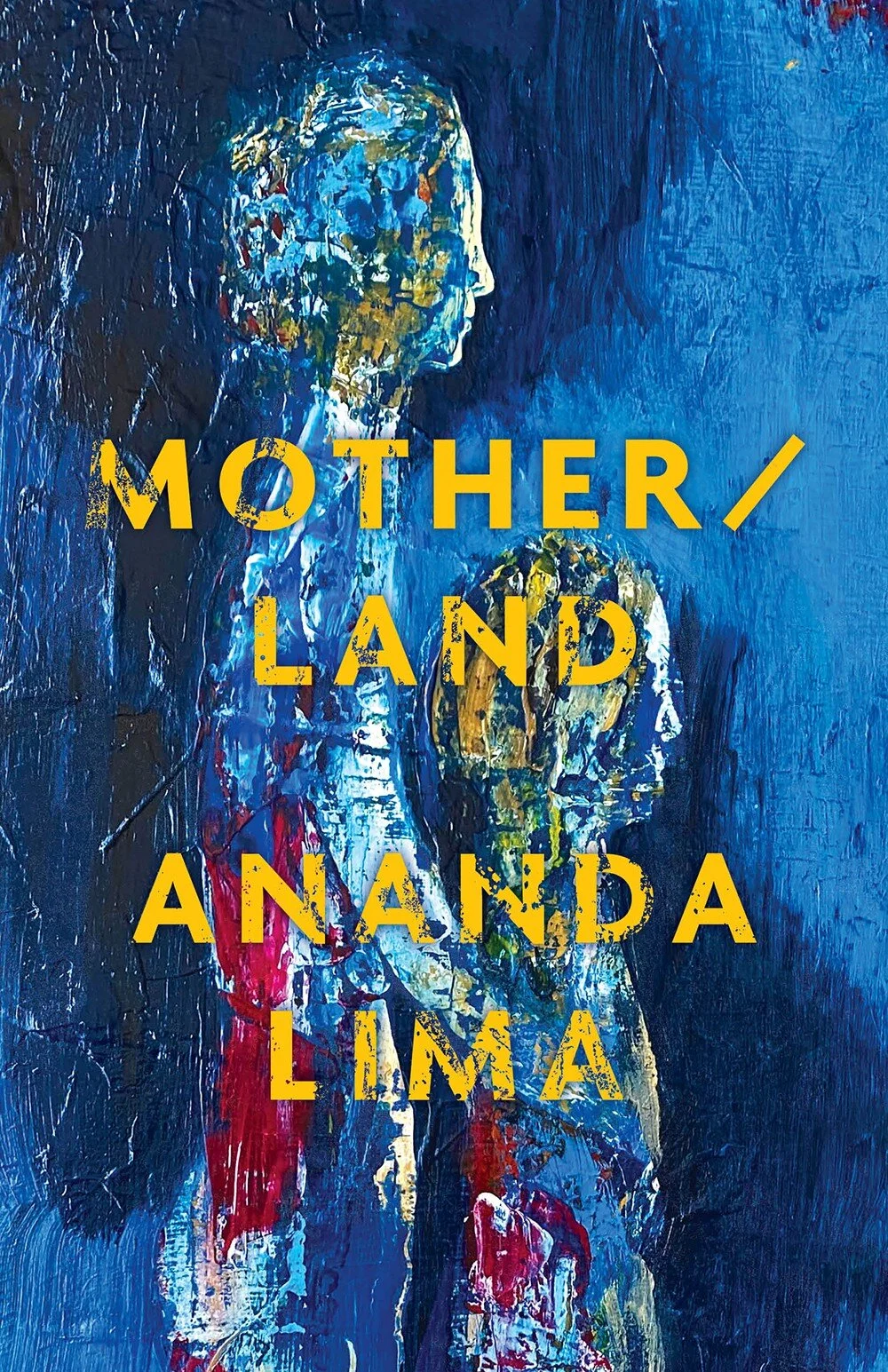

Heartfelt and honest, Ananda Lima’s debut poetry collection Mother/land is at once a song of motherhood, a lament for home, and a meditation on the immigrant struggle to find true belonging in the U.S. As an immigrant from Brazil and parent of an American-born son, Lima uses her poems to reflect on both grief over her personal experiences and the fierce, self-sacrificial love for her child that brought her through those difficulties.

In Mother/land, an interest in divisions and multiplicity permeates both form and content — a focus that is perhaps best illustrated in the stylistic rendition of the title itself. Lima’s simple slash symbol explodes the word “motherland” into several layers of encounters with grief. Thematically, Lima grapples with a series of dualities: past and present, Brazil as her homeland and America as her new land, identities as an immigrant and mother. Her poems construct a smooth, moving interplay between autobiography, national history, and anticipation of the future for her son.

While many poems explore the tensions between immigrant identities, I was also especially interested in the way Lima weaves together different kinds of language — Portuguese, biblical language, dialogue associated with settings ranging from airport security checkpoints to architecture tours. In “Seven American Sentences,” Lima uses language from the Genesis creation story in conjunction with shameful aspects of the United States’s human rights record, coolly drawing attention to the discrepancy between proclaimed American ideals and the reality of injustice.

Thematically, Lima grapples with a series of dualities: past and present, Brazil as her homeland and America as her new land, identities as an immigrant and mother.

Beyond detailing Lima’s modern-day experiences with feeling “other” in the U.S., Mother/land draws extensively on American history as part of Lima’s internal wrestling with the reality of the U.S. as her new country, far removed both geographically and socially from her motherland. In “Cleaning the Colonial,” Lima repurposes the language of colonialism when addressing her house, almost like a reclamation of that act of possession: “I occupy your hollow rooms and populate them with private song.” She also confronts the reality that, despite the immigrant’s enduring struggle for a sense of belonging, the once independent strands of history between herself and the foreign country she moved to have since become inextricable:

By now we understand

you don’t really belong

to me

and I don’t really belong

but we have come to accept

that our histories have commingled

Lima compellingly evokes the complexity of the immigrant experience by portraying blurred and unclear divisions. In “monday between [[impeachment or [something]] and the end of the world],” we visualize the lack of an audible distinction between words:

I can’t

tell the difference

morning | mourning

luto | luto…

perfume | perfume

Lima repurposes the language of colonialism when addressing her house, almost like a reclamation of that act of possession.

One element that most powerfully distinguishes Mother/land from other immigrant narratives to me is the collection’s resounding musicality. Repetitions of similar-sounding Portuguese words drive poems like “every moon,” which read like chants or songs that are at once artful and unrestrained, metered and intense, brimming with emotion and soul. Similarly, in the collection’s final poem, “Berimbau,” the infusions of Portuguese add a musical quality as rhythmic and percussive as the “beat of running” and the “meat and bones cracking / dirt” that the poem describes, culminating in a rapturous ending:

Bimba Toque de luna we

follow o compaço de aço o compaço do passo

o compaço da culpa do

Sol

Meanwhile, “Translation” and “Moving Sale” experiment ambitiously with form, re-imagining the structures of the sestina and the pantoum by replacing moments of pure repetition with Portuguese translations. Additionally, though I was initially skeptical of Lima’s enjambment choices, I came to appreciate how her collection-wide style of short broken lines seems to evoke the effort it takes to learn and speak English as a second language (with her own language itself remaining ever graceful and poignant):

I

was afraid for him

speaking anything other

than the unofficial

official language

of this land

which is not my land

despite the claims

it makes in song

I gave in

and spoke to him

in my broken

version of his

language

Repetitions of similar-sounding Portuguese words drive poems like “every moon,” which read like chants or songs that are at once artful and unrestrained, metered and intense, brimming with emotion and soul.

Since the U.S. fails to live up to its ideals as described in songs — the land of the free, a country that welcomes all and celebrates diversity — Lima writes her own poems into song. Whether immigrants ourselves or not, Mother/land can speak to the many of us who have grappled with existing in a national context that puts up barriers on so many fronts, from language to physical movement. Lima’s collection resounds with both incantations in her mother tongue and with English refrains that burn blue with longing, with the search for home.

MOTHER/LAND

By Ananda Lima

90 pp. Black Lawrence Press. $15.95.

Order here.

Esther Sun is a Chinese-American writer from the Silicon Valley. A two-time Pushcart Prize nominee, she received a Gold Medal Portfolio Award in the 2021 Scholastic Art and Writing Awards and has published poems in DIALOGIST, Cosmonauts Avenue, Pacifica Literary Review, and elsewhere. She attends Columbia University.